Children, Influencers, and Impulse Buying Online

You may have seen news outlets reporting on the trend...

TeacherLists Surpasses One Million School Supply Lists on its Platform

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

PRESS RELEASE

TeacherLists

100...

What Teachers Want You to Know About Back-to-School

Teachers have a difficult job, and one that doesn’t...

Books, Movies, and TV Shows to Binge: Parent Recommendations

Are you a book worm, or do you prefer watching...

How to Talk to your Child About Their World

Help your child feel safe while staying informed with...

Tips and Tricks for a Successful Back-to-School Routine

Back-to-school season is in full swing! Whether your...

No Image found

8 Books for Overcoming Back-to-School Anxiety

Many kids feel a whirlwind of emotions before the new school...

What is the Metaverse—and should you be concerned?

What do you call an all-encompassing online world your...

10 Ways to Honor Memorial Day with your Children

Check out these tips to honor Memorial Day, shared...

Mother’s Day “Mom-Me” Time Activities from Real Moms

Me time activities from real moms, just in time for Mother’s...

Teacher Appreciation Week: The Do’s and Don’ts

Check out these tips for how to, and how not to, thank...

Standardized Tests: Tips and Tricks to Prepare Your Children

Ease test anxiety with these tips and tricks!

5 Tips to Promote Social-Emotional Development at Home

Social-emotional development is fundamental for success....

Screen Time: the good, the bad, and the balance

Unlock the benefits to screen time. The key is striking...

The 10 Most Boring (But Awesome!) Gifts for Teachers

Believe it or not, teachers love receiving school supplies...

Set Kids Up for School Success: Healthy Habits Parents Can Teach Their Kids

By establishing important eating, sleeping, and learning...

7 Smart Tips To Help You Ace Back-to-School Shopping

On paper, the idea of back-to-school shopping is exciting...

Shop Your Supply Lists During Tax-Free Weekends

Take advantage of the back-to-school timing of states'...

Talking to Kids About Anti-Racism and Race Relations

Conversations with kids about race relations can be hard,...

Science for Kids: 28+ STEM Activities To Do at Home

Step-by-step instructions and materials lists for family-friendly...

Parents: You Should Know This Internet Slang

There's a good chance a lot more kids will be spending...

After-School Snacks: Healthy Options for Kids

Fun ideas for healthy after-school snacks kids will...

Understanding Report Cards: A Guide for Parents

Letter grades are being replaced by number systems...

Learning Styles Quiz: What Is Your Child's Learning Style?

Understanding how your child learns can reduce frustration...

Helping Students Adjust to the New School Year: Teacher Tips for Parents

Back-to-school tips for families

School Success - 10 Ways Parents Can Help: Teacher Tips for Parents

School Success—10 Ways Parents Can Help

Teachers...

10 Ways To Help Kids Handle Back-to-School Anxiety: Teacher Tips for Parents

10 Ways To Help Kids Handle Back-to-School Anxiety:...

Make Parents Your Partner: Teacher Tips for Parents

Teachers: Make Parents Your Partner

Building strong...

Homework Tips for Parents: Teacher Tips for Parents

Homework Tips for Parents

When the last bell rings...

No Image found

Student Goal Setting: 3 Teacher Tips for Parents

Student Goal Setting: 3 Steps to Success

January is a great...

At-Home Learning Tips for Parents: Teacher Tips for Parents

At-Home Learning Tips for Parents

While teachers play...

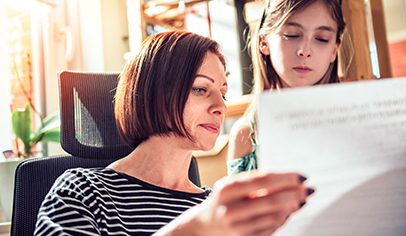

Guide to Parent-Teacher Conferences: Teacher Tips for Parents

Why Attend a Parent-Teacher Conference?

Parent-teacher...

No Image found

The Top Teacher Gifts You Can Find on Amazon Right Now

The top gifts for teachers this holiday season. Apparel,...

No Image found

Black Friday Deals for Everyone on Your List

Kittaya Mangruan/123RF

Whether you’ll be getting...

No Image found

How to Use One-Click Shopping Right From Your List

You've found your child's supply list and now you want...

No Image found

How Parent Groups can help their Schools with TeacherLists

Are you a Parent or part of a Parent Group (PTO/PTA/PTSO/HSA,...

No Image found

How To Use Amazon To Purchase TeacherLists Wish List Items

Step-by-step instructions to make donating classroom...

No Image found

What You Need to Know About Back-to-School Shopping In Your State

There are so many funny blogs out there about what...

No Image found

How To Find Your School's Supply Lists on TeacherLists

Find your child’s school supply lists and classroom...